"You speak English so well… "

— these were the words I once got told during an job interview in London in 2006. I had just moved to Britain, and wanted to work while I studied for my solicitor qualifications. The interviewer seemed genuinely surprised, as if my Pakistani identity and English fluency were somehow contradictory. What they didn't understand was the complicated history behind my flawless English, and the cultural price I had paid for this "compliment."

There was a time when I wore my English fluency like a badge of honour. Growing up in Pakistan, I remember the subtle hierarchy: English medium schools at the top, Urdu medium somewhere below. I was proud to belong to the former, to speak without the "typical Pakistani accent," to read Shakespeare with more ease than Ghalib. I thought this made me sophisticated, cosmopolitan, and better prepared for a global future.

I was wrong. As I grow into these older years, into a mind of a creative academic, I see I am the one at the bottom. I see now how deeply I had internalised the postcolonial mindset that positioned the coloniser's tongue above my own.

Now in my 50s, pursuing a PhD in creative writing in Britain, I find myself in a strange liminal space. I'm writing about my culture in a language that, whilst I've mastered it, was never truly mine to begin with. And in so many ways, the story I am trying to tell feels flat against the singular texture of English, as opposed the the floral extravagance of not just Urdu but the culture I seek to write about.

The irony doesn't escape me: I study creative expression while feeling fundamentally disconnected from the most authentic form of expression I could have had.

elitism of language

In Pakistan, language has always been political and social. The division between English medium and Urdu medium education isn't merely pedagogical—it's a class marker, a remnant of colonial structures that were never dismantled after independence. Those who could afford English medium schools entered a different social stratum, gained access to different opportunities, moved in different circles.

I benefited from this system. My family made sure I would be on the "right" side of this divide. But what seemed like advantage was also a subtle form of erasure.

When I looked down on those who struggled with English, when I rolled my eyes at "broken English," when I felt superior for being able to converse fluently with foreigners—I was participating in my own cultural diminishment. I was accepting the premise that the coloniser's ways were inherently superior to our own. And I am ashamed of this.

the post-memory of language loss

Scholars might call this "post-memory"—the relationship that the generation after bears to the trauma experienced by those who came before. I didn't live through colonial rule, but I inherited its aftermath, its hierarchies, its ways of determining worth. Post-memory seems to be the backbone of my writing and research and as I delve deeper into it, the loss of language is an inescapable reality.

The loss I feel isn't just my own—it's intergenerational, a wound that opened before I was born but that I've been taught to ignore or even celebrate.

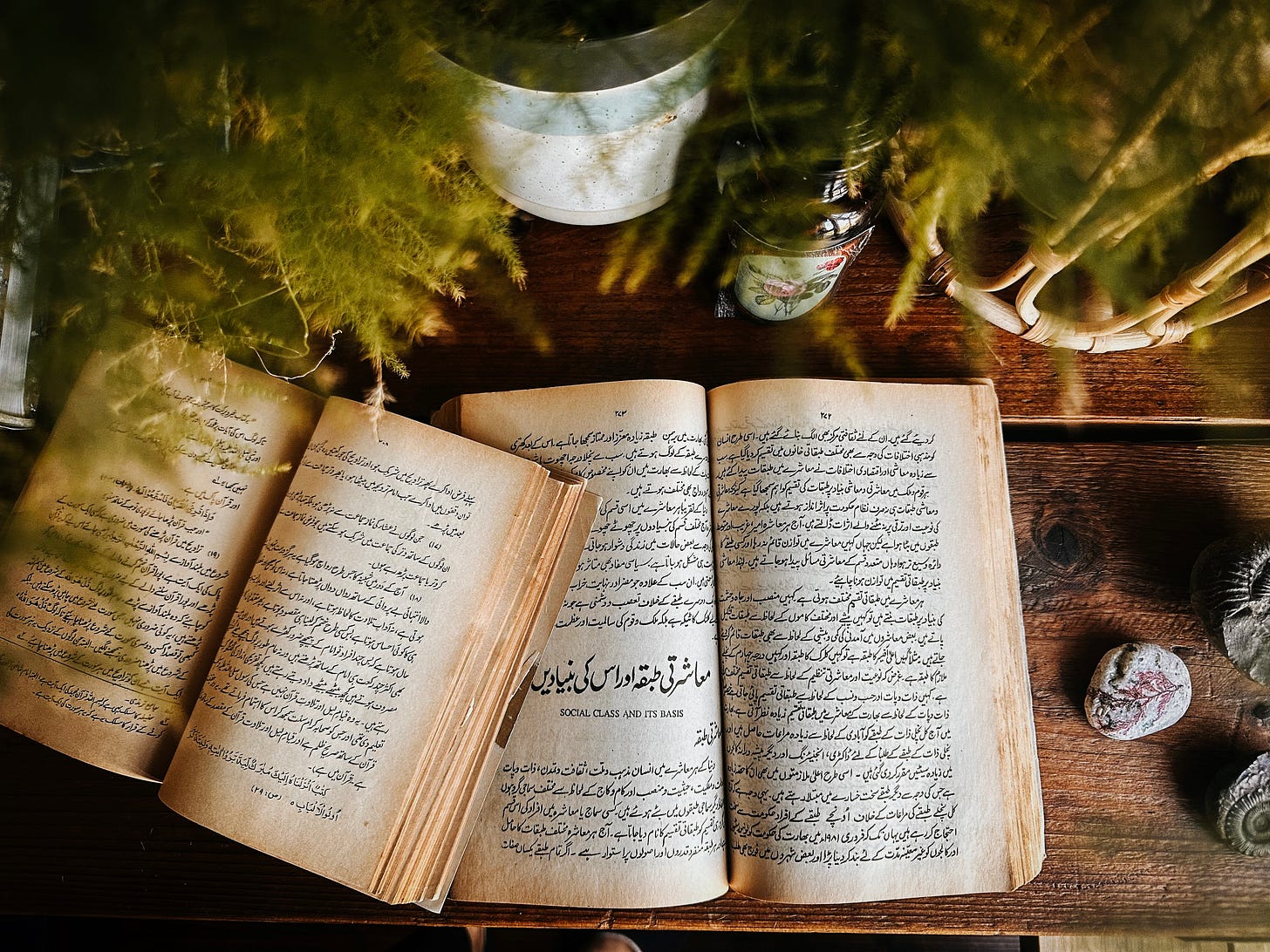

When I struggle to read Urdu poetry now, when I must rely on translations to access the literary heritage that should have been my birthright, I feel this loss deep in my heart — soul — being.

I am othered from my own language. The tongue that should feel most natural to me has become foreign, distant, difficult.

no one asks about what was lost

Living in Britain, I'm struck by how little anyone seems to care about this loss. My English proficiency is taken for granted—it's expected, unremarkable. No one wonders what I had to give up to acquire it. No one asks about the multiverse of wonderful literature and poetry that remains inaccessible to me in its original form. No one realises how hard it is for me to feel accepted in my own language, while I speak theirs. I speak Urdu, sure, but I can’t read it as I should.

There's a certain cruelty to this indifference. The system demanded that we adopt the coloniser's language to be taken seriously, then refused (and still refuses) to acknowledge what that adoption cost us.

My relationship with language embodies what Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o called the "cultural bomb" of colonialism:

"The effect of a cultural bomb is to annihilate a people's belief in their names, in their languages, in their environment, in their heritage of struggle, in their unity, in their capacities and ultimately in themselves."

finding my voice in the fragments

So where does this leave me as a writer trying to tell stories about my culture? How do I authentically represent experiences when the most authentic linguistic tool has been partially taken from me? Could I have worked harder to accept my language inheritance more graciously when I was younger?

Maybe the answer lies not in lamenting what was lost but in writing from this very space of in-betweenness. Perhaps my unique perspective—of someone who straddles languages, who knows what it means to both gain and lose through language—offers something valuable.

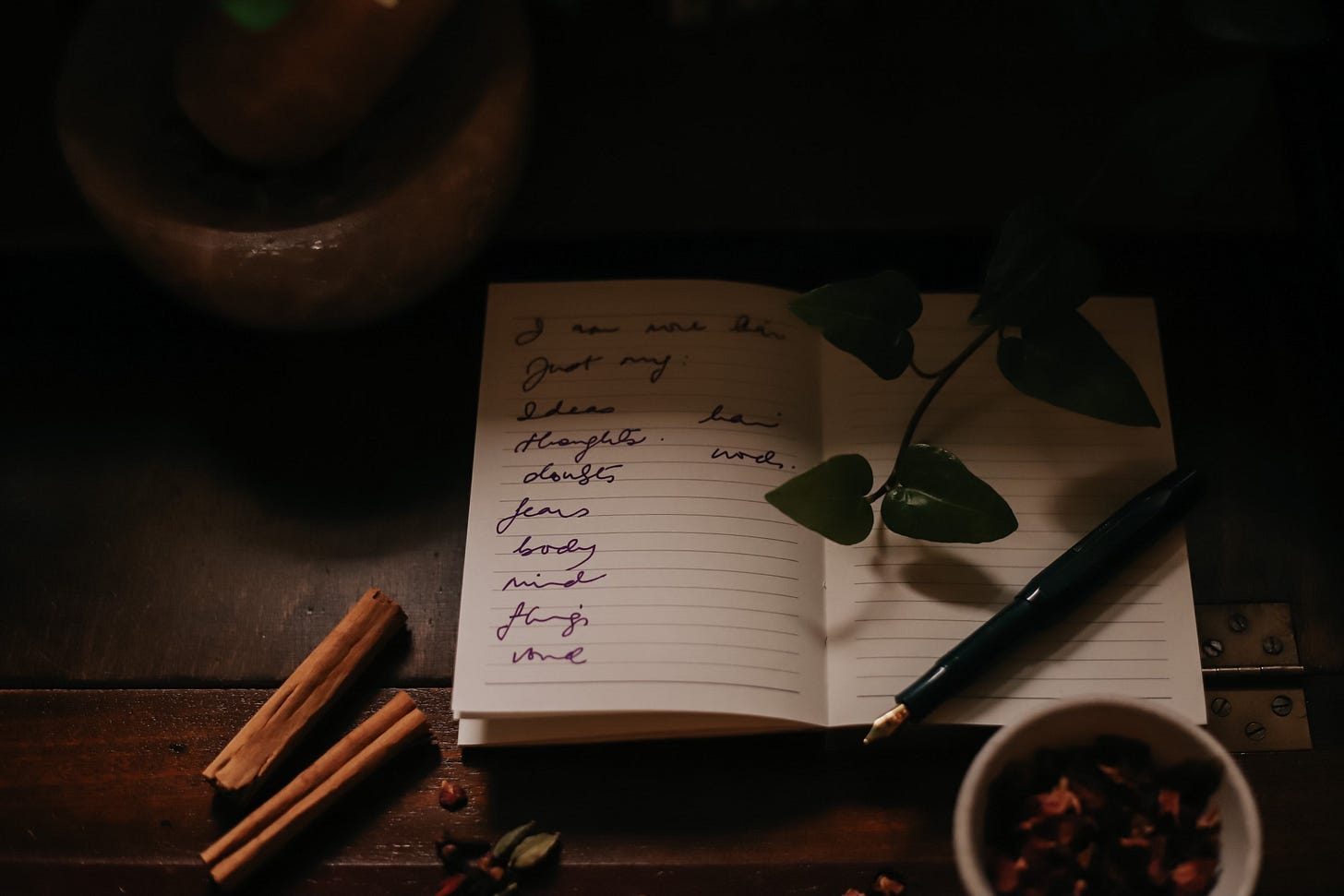

I am here trying to wade my way through this mess by using broken sentences, writing English from right to left, messing with syntax, using Urdu words without apology or italics — this is my way of owning my broken belonging with my own mother tongue, the sadness/anger/disappointment expressed through fragmented craft decisions. I recently I began reading Root Fractures, a collection of poems by Diana Khoi Nguyen. Finding a poem there written entirely in Vietnamese, without any excuse, made me think of how the theme within the collection deeply resonates with me. As well as the how she examines what takes root after a disaster (on our lives and those of our ancestors) and ‘how we can make a story out of the broken pieces of our lives.’

Maybe the fragmentation itself is the story.

The way we Pakistani writers of a certain class and generation must piece together our identity from multiple sources—taking what we can from our mother tongue whilst acknowledging the imprint the coloniser's language has left on us.

I'm learning to see my relationship with language not as a failure but as a complex inheritance. I'm learning to forgive myself for the pride I once felt in my English and the disdain I held for Urdu. I was a child absorbing the values around me.

As I work on my creative writing PhD, I'm attempting to reclaim what I can. I'm incorporating Urdu phrases, concepts, and sensibilities into my English writing. I'm reading translations of Urdu works and studying the language with new determination.

I’m trying to relearn my own language.

This isn't a complete solution. The gap will always remain. But maybe in acknowledging it, in writing about it, in refusing to pretend it doesn't exist — I'm taking the first step toward healing.

And, just maybe, in sharing this journey, I'll find others who understand this peculiar grief —

—the grief of being othered from your own language before you even had the chance to fully claim it.

I can't begin to explain how deeply this resonated with me. Thank you for articulating this struggle, my struggle, so beautifully. As a third culture kid, and a Canadian currently visiting Pakistan, this is exactly what I'm feeling these days.

Thank you for writing this Sumayya! This is exactly how I feel! Your drive to relearn it makes inspires me to bring Urdu back into my life as well. I’ve been struggling with sharing it with my kids and teaching them. Urdu was always so horribly looked down upon in school and I want it to be an enjoyable experience for my own children. It’s very hard though with the lack of resources.